Res Dev Med Educ. 13:24.

doi: 10.34172/rdme.33237

Original Article

The relationship between the stress of parental and teacher academic expectations and student anxiety: The mediating role of social skills

Mahdi Ahmadi Varzaneh Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, 1

Mahmoud Reza Shahsavari Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 2, *

Shokoufeh Mousavi Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, 1

Author information:

1Department of Psychology, Payame Noor University, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Sociology, Payame Noor University, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Background:

Elevated academic expectations imposed by parents and teachers can adversely affect student well-being and contribute to heightened anxiety levels. This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of social skills in the relationship between the stress of parental and teacher academic expectations and anxiety in high school students.

Methods:

This investigation employed a cross-sectional, correlational descriptive research design. The statistical population encompassed all high school students enrolled in Isfahan during the 2022-2023 academic year. A cluster sampling technique was utilized to select a sample of 225 students. Data collection was facilitated through the administration of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ), Social Skills Rating System-Secondary Students Form (SSRS-SS), and Academic Expectations Stress Inventory (AESI). The proposed theoretical model was assessed using structural equation modeling with the aid of SPSS-23 and SmartPLS-4 software.

Results:

The findings revealed a positive and significant correlation between both parental (r=0.44, P<0.01) and teacher (r=0.41, P<0.01) academic expectations and student anxiety. Conversely, a negative and significant correlation was observed between parental (r=-0.36, P<0.01) and teacher (r=-0.42, P<0.01) expectations and students’ social skills. Furthermore, social skills demonstrated a negative and significant association with student anxiety (r=-0.31, P<0.01). Notably, social skills mediated the relationship between parental and teacher academic expectations and student anxiety (P=0.001).

Conclusion:

High academic expectations from parents and teachers can increase student anxiety. However, strong social skills can buffer this negative impact. To improve student well-being, interventions should focus on both academic success and social-emotional development.

Keywords: Anxiety, Academic expectations stress, Social skills, Students

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the

original authors and source are cited. No permission is required from the authors or the publishers.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Introduction

Adolescence is a developmental transition characterized by profound biological, cognitive, psychological, and social changes. These transformations, influenced by familial and peer dynamics, often lead to interpersonal challenges.1 Anxiety is a prevalent issue during this period, manifesting in various behavioral and physical symptoms, including sleep disturbances, academic difficulties, and social withdrawal.2 The complex interplay of biological, psychological, and environmental factors contributes to the development of anxiety in adolescence. Exposure to conflicting messages during puberty can heighten feelings of insecurity and vulnerability, potentially leading to chronic or episodic anxiety.3 Adolescents’ heightened capacity for future-oriented thinking can exacerbate anxiety. The cognitive process of worry, involving intrusive thoughts about potential negative outcomes, is a core component of anxiety.4 This preoccupation with hypothetical threats can lead to a state of hypervigilance, negatively impacting overall well-being.

The rapid developmental transformations characteristic of adolescence exert a profound influence on interpersonal relationships, particularly those with parents and teachers, frequently resulting in heightened conflict and anxiety.5 Families occupy a central role in shaping adolescent development, and parental expectations and communication styles can significantly impact adolescent well-being.6 Unrealistic expectations and ineffective communication strategies can contribute to elevated anxiety and stress levels. Research suggests that approximately 25% of adolescents experience anxiety, with girls exhibiting higher levels of anxiety compared to boys.7 Furthermore, adolescents grappling with anxiety are more likely to manifest symptoms of depression.8 Anxiety has also been associated with deficient problem-solving skills and an intolerance of ambiguity.9 Studies have demonstrated that academic pressures constitute a substantial source of anxiety for numerous adolescents.10,11

The complexities of the adolescence stage often lead to a sense of disconnection between adolescents and their parents, as evolving self-concepts may diverge from parental expectations.12 The biological changes of puberty can exacerbate this tension, contributing to increased emotional reactivity and rebellious behaviors. While stress is a universal human experience, adolescents often encounter heightened levels of stress due to the multifaceted challenges of this developmental stage.13,14 Common psychological difficulties during adolescence include depression, anxiety, and mood disorders, which can profoundly impact cognitive and emotional functioning.15 The adolescent desire for autonomy frequently clashes with parental and teacher expectations. Idealized perceptions of adolescent behavior can create dissonance and conflict within these relationships. As adolescents transition into adulthood, societal expectations shift, requiring parents to adapt their parenting styles.16 Effective parent-adolescent relationships are essential for navigating these challenges.17 Parental and teacher expectations can significantly influence adolescent development, with positive or negative consequences depending on their nature and management.18 Research indicates that teacher expectations, in particular, can shape student behavior and academic outcomes.19,20

Adolescence represents a critical juncture for the cultivation of social skills as individuals navigate peer interactions and school environments. Adolescents confront a diverse array of challenges, including identity crises, negative self-perception, social deviance, depression, and aggression. To foster resilience and success, adolescents must develop robust social competencies. Given the substantial role that parental and teacher expectations, in conjunction with social skills, play in adolescent stress, predicting anxiety levels within this population is crucial. Comprehending the interplay between these factors and anxiety is essential for the development of effective interventions. If left unchecked, anxiety can have significant detrimental consequences for adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Given the pivotal role of adolescents in shaping the trajectory of society, addressing their concerns, particularly anxiety, is imperative. While a substantial body of research exists on adolescent anxiety, relatively few studies have specifically examined the relationships among parental and teacher expectations, social skills, and anxiety. Consequently, this study aims to investigate the mediating role of social skills in the association between academic-related stress stemming from parental and teacher expectations and adolescent anxiety.

Methods

This investigation employed a cross-sectional, correlational research design. The statistical population encompassed all high school students enrolled in Isfahan during the 2022-2023 academic year. The sample comprised 225 male and female high school students selected from four high schools using a cluster sampling technique. The sample size was established based on the number of research variables. Given the variables involved in this study, a total of 220 samples was deemed adequate. To account for a projected attrition rate of 10%, the estimated sample size was adjusted to 242. Following the removal of incomplete questionnaires, the final sample comprised 225 participants, with 17 questionnaires discarded due to incompleteness. Participants were high school students aged 13 to 18 years who provided written informed consent. Eligibility criteria stipulated that participants self-reported being free from any diagnosed physical or mental health conditions. To further ensure participant eligibility, researchers conducted face-to-face interviews to verify self-reported health information. Exclusion criteria included refusal to participate or incomplete questionnaire data. A total of 242 questionnaires were distributed among the students, and after excluding incomplete questionnaires, 225 questionnaires were analyzed.

Instruments

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ)

The PSWQ is a self-report measure designed to assess the trait of worry. Comprising 16 items that evaluate worry frequency and intensity across various situations, the PSWQ effectively differentiates individuals with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) from those without. Its self-report format allows participants to rate the extent to which each item aligns with their experiences, using a typical Likert scale of 1 to 5.21 The Persian version of PSWQ is a validated measure of worry, demonstrating high reliability and validity (α = 0.89).22 Dehshiri et al22 have shown that the Persian version of the PSWQ is a reliable and valid measure of worry in Iranian college students.

Academic Expectations Stress Inventory (AESI)

The AESI is a self-report measure designed to assess the level of academic stress experienced by students due to expectations placed upon them by both themselves and their parents and teachers. Consisting of nine items, the AESI employs a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Never True” to “Almost Always True” to evaluate the frequency and intensity of stress-inducing expectations. The AESI comprises two primary factors: Expectations of Self and Expectations of Parents/Teachers, providing insights into the specific sources of academic stress. The inventory has demonstrated reliability and validity in measuring academic stress, with scores reflecting the overall level of stress experienced.23 Habibi Asgarabad et al24 reported the reliability of this questionnaire based on Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Social Skills Rating System – Secondary Students Form (SSRS-SS)

The SSRS-SS is a 39-item measure assessing core social skills domains: self-control, cooperation, empathy, and assertion. The self-control subscale encompasses behaviors in both conflict (e.g., responding to teasing) and non-conflict (e.g., turn-taking) situations. Cooperation is evaluated through behaviors like sharing and rule-following. Empathy is assessed by behaviors reflecting concern for others, and assertion by initiating interactions. A three-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often) is used to rate behavior frequency, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 78.25 The SSRS-SS is a validated measure of social skills. Eslami et al26 demonstrated the acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81) and construct validity of the Persian version of the SSRS-SS.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed using SPSS-23 and SmartPLS-4 software. Prior to conducting the SEM analysis, descriptive statistics were calculated, including Pearson correlations, skewness, and kurtosis. Pearson correlations were computed to assess the relationships between variables, while skewness and kurtosis were examined to evaluate the normality of the data distribution.

Results

The current study involved 225 high school students with a mean age of 16.45 ± 2.60 years. The sample consisted of 124 (55.1%) females and 101 (44.9%) males. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of the variables. Based on the skewness and kurtosis values, the normality assumption of the data was examined. As shown in the table, the skewness values fell within the range of -3 to 3, and the kurtosis values were within the range of -2 to 2. Therefore, the normality assumption was supported. Furthermore, the results indicated a positive correlation between parental and teacher academic expectations and student anxiety. In contrast, there was a negative and significant correlation between students’ social skills and anxiety (Table 2).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations (SD), skewness, and kurtosis, of the study variables

|

Variables

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Skewness

|

Kurtosis

|

| Anxiety |

64.37 |

8.45 |

2.25 |

-1.69 |

| Social skills |

40.77 |

6.30 |

0.74 |

-0.57 |

| Parental academic expectations |

2.78 |

0.71 |

-0.17 |

-0.39 |

| Teacher academic expectations |

2.95 |

0.47 |

0.09 |

-0.46 |

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients among the study variables

|

Variables

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

| 1- Anxiety |

1 |

|

|

|

| 2- Social skills |

-0.31** |

1 |

|

|

| 3- Parental academic expectations |

0.44** |

-0.36** |

1 |

|

| 4- Teacher academic expectations |

0.51** |

-0.42** |

0.21* |

1 |

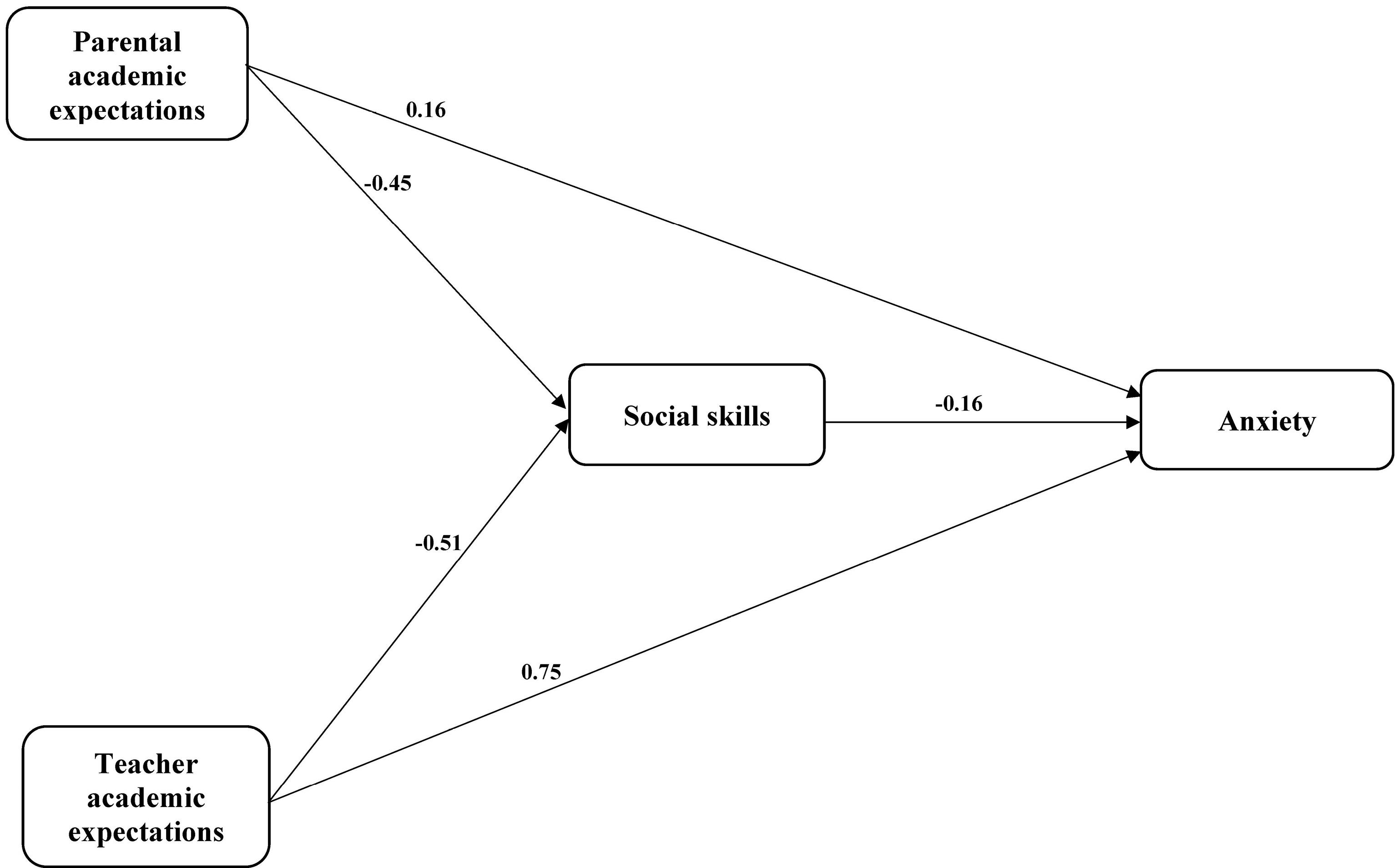

The predictive relevance of the structural model was assessed using the cross-validated redundancy (CV-RED) criterion. Positive CV-RED values indicate an acceptable model fit. For endogenous constructs, CV-RED values are typically categorized as weak ( ≤ 0.2), moderate (0.21-0.35), and strong ( ≥ 0.35). As shown in Table 3, the CV-RED values for the endogenous constructs in our model were below 0.35, suggesting a moderate predictive relevance. Moreover, all CV-COM values were positive, further supporting the measurement model. The R-squared value indicated that 58.0% of the variance in anxiety was explained by social skills and parental and teacher academic expectations. Figure 1 indicates the research model.

Table 3.

Results related to model quality test, redundancy index, and good indicator

|

Variables

|

CV-RED

|

CV-COM

|

R2

|

| Anxiety |

0.16 |

0.23 |

0.58 |

| Social skills |

0.22 |

0.23 |

0.80 |

| Parental academic expectations |

- |

0.31 |

- |

| Teacher academic expectations |

- |

0.06 |

- |

Figure 1.

Research model in standard mode

.

Research model in standard mode

Table 4 presents the standardized path coefficients to evaluate the hypothesized direct and indirect effects. Results indicate a significant negative relationship between social skills and anxiety among students (β = -0.16, P = 0.019). Additionally, positive relationships were found between both parental (β = 0.16, P = 0.011) and teacher academic expectations (β = 0.75, P = 0.001) and student anxiety. Furthermore, negative relationships emerged between parental (β = -0.45, P = 0.001) and teacher academic expectations (β = -0.51, P = 0.001) and students’ social skills. Importantly, the model supported a significant mediating effect of social skills on the relationship between parental and teacher academic expectations and student anxiety (P = 0.010).

Table 4.

Path coefficients of direct and indirect relationship between the study variables

|

Path

|

β

|

t

|

P

|

| Parental academic expectations of anxiety |

0.16 |

2.68 |

0.011 |

| Teacher academic expectations of anxiety |

0.75 |

7.30 |

0.001 |

| Parental academic expectations of social skills |

-0.45 |

-7.09 |

0.001 |

| Teacher academic expectations of social skills |

-0.51 |

-8.47 |

0.001 |

| Social skills to anxiety |

-0.16 |

-2.30 |

0.019 |

| Parental academic expectations of anxiety through social skills |

0.23 |

2.18 |

0.010 |

| Teacher academic expectations of anxiety through social skills |

0.22 |

2.21 |

0.010 |

Discussion

This investigation explored the mediating role of social skills in the relationship between academic-related stress, originating from parental and teacher expectations, and anxiety levels among high school students. The results revealed a significant positive correlation between parental academic expectations and student anxiety. These findings align with previous research by Zheng et al,27 and Peleg et al.28 To explain these findings, it is important to consider that adolescence is a critical period marked by significant cognitive and structural changes. Families often serve as a source of stress during this time, negatively impacting adolescents’ mental health.7 Worry is a coping mechanism employed to manage ambiguous emotions and anxieties about future events. Compared to individuals with healthy coping mechanisms, those unable to tolerate ambiguity and experiencing high levels of anxiety and worry may resort to maladaptive behaviors, leading to impaired mental health. This reciprocal relationship suggests that adolescents with parents who hold unrealistic expectations are more likely to experience worry, focus excessively on future events regardless of their probability, and exhibit a low tolerance for ambiguity, consequently experiencing higher levels of psychological distress. Individuals facing psychological distress may struggle to withstand pressure and may be unable to effectively cope with problems. In general, high levels of parent-child conflict and weak emotional bonds contribute to increased anxiety in adolescents.27 Moreover, families with unrealistic expectations often exhibit other maladaptive cognitive patterns, such as rigid and inflexible beliefs that hinder democratic decision-making and negative interpretations of events, which can lead to negative emotions. Consequently, adolescents who experience constant conflict with their parents may feel helpless, leading to symptoms of depression such as feelings of hopelessness, sadness, and anxiety.12

The results indicated a significant positive correlation between teachers’ unrealistic academic expectations and student anxiety. These findings align with previous research by Hollenstein et al.29 To explain these findings, it can be argued that teachers form expectations about students based on initial interactions and information from school records. Subsequently, teachers exhibit different behaviors toward students based on these expectations. This teacher’s behavior is reciprocated by students.18 Teachers with unrealistic expectations create negative classroom environments and communicate these expectations to students through feedback, thus influencing student behavior and increasing anxiety.29 Student anxiety is closely linked to school-related factors, highlighting the need for guidance and counseling services. Teachers with strong role-modeling abilities can significantly impact students’ personal development. While reasonable expectations can motivate students to strive for higher achievement and improve performance, excessive expectations can lead to student stress and negatively impact their mental health, including anxiety.

Furthermore, the results demonstrated a significant negative correlation between social skills and anxiety among students. These findings align with previous research by Lai et al.30 To elucidate these findings, it can be argued that contemporary life necessitates a range of competencies that influence an individual’s decision-making in the face of various events and circumstances. Human abilities can be categorized into physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains. Each of these abilities exerts a profound impact on an individual’s life and future. Among these, social skills are widely recognized as particularly important.25 Our findings suggest a negative correlation between social skills and anxiety, indicating that social skills can predict lower levels of anxiety. The inability to effectively express emotions can compromise adolescents’ mental, physical, and psychological well-being, challenging their ability to form and maintain social relationships, especially those requiring social skills. Individuals experiencing anxiety often become preoccupied with their thoughts, leading them to avoid social interactions.30 Adolescents with lower levels of anxiety tend to form more social connections, while those with higher levels of anxiety are more likely to avoid social situations and the associated skills.

The results indicated that students’ social skills mediated the relationship between parental and teacher academic expectations and student anxiety. To explain these findings, it can be argued that unrealistic parental expectations may lead children to exhibit poor social skills. Fearing exposure of their perceived shortcomings, they may avoid close relationships with friends and peers and often decline to participate in group activities.25 These avoidant behaviors can eventually contribute to anxiety. Consequently, unrealistic parental expectations, coupled with parental criticism for failing to meet these expectations, can erode a child’s self-esteem, leading to a decrease in their social skills.

Over time, students become familiar with their teachers’ characteristics and often develop sensitivities to perceived unrealistic expectations in the classroom. Many students’ stress and misinterpretations of teachers’ behaviors stem from a lack of understanding of teachers’ responsibilities.29 This can lead to students forming unrealistic expectations of their teachers. If students focus solely on the demanding aspects of a teacher’s behavior, they may become overly preoccupied with trying to elicit positive responses, as these misinterpretations can increase their anxiety. In fact, students who are more sensitive to teachers’ behaviors are more likely to form negative cognitive evaluations of teachers’ expectations and establish non-intimate relationships with their teachers, contributing to higher levels of anxiety.18 Such a classroom environment, characterized by a lack of intimacy and connection with peers, can further exacerbate students’ anxiety.

The cross-sectional design of this study precludes the establishment of causal relationships between variables. Although correlations were identified among academic expectations, social skills, and anxiety, determining the direction of influence or accounting for potential temporal factors is not feasible. Moreover, the study’s focus on high school students in Isfahan restricts the generalizability of findings to other populations, as cultural, socioeconomic, and regional disparities may influence the observed relationships. Finally, the reliance on self-report measures introduces potential biases, such as social desirability and recall bias, which may distort participants’ reported levels of anxiety, social skills, and academic stress.

To address the limitations of the present study and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between academic expectations, social skills, and anxiety, future research could employ a longitudinal design to establish causality, conduct experimental studies to manipulate variables and measure their impact, include diverse populations to enhance generalizability, incorporate alternative assessment methods to reduce the reliance on self-report measures, explore additional mediating and moderating factors, and develop and evaluate interventions aimed at improving social skills or reducing the negative impact of high academic expectations on anxiety.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the complex interplay between parental and teacher expectations, social skills, and student anxiety. The positive association between academic expectations and anxiety suggests that excessive pressure from both parents and teachers may contribute to elevated levels of anxiety among students. Conversely, the negative relationship between academic expectations and social skills indicates that high-pressure environments may hinder the development of essential interpersonal competencies. Crucially, the mediating role of social skills highlights their importance in mitigating the adverse effects of academic expectations on student mental health. These results emphasize the need for interventions that promote both academic achievement and social-emotional development to foster overall student well-being.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the educators, parents, and students who participated in this study, providing invaluable insights into their experiences.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study was granted ethical approval by the Ethical Committee of Payame-Noor University (approval code: IR.PNU.REC.1402.210).

References

- Jimenez AL, Banaag CG, Arcenas AM, Hugo LV. Adolescent development. In: Tasman A, Riba MB, Alarcón RD, Alfonso CA, Kanba S, Ndetei DM, et al, eds. Tasman’s Psychiatry. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 1-43. 10.1007/978-3-030-42825-9_106-1.

- Santosa B, Marchira CR, Sumarni S, Rianto BU, Supriyanto I. The association between anxiety and professionalism in residents of ENT specialist training program in the Faculty of Medicine, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia. Res Dev Med Educ 2017; 6(2):58-61. doi: 10.15171/rdme.2017.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Narmandakh A, Roest AM, de Jonge P, Oldehinkel AJ. Psychosocial and biological risk factors of anxiety disorders in adolescents: a TRAILS report. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021; 30(12):1969-82. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01669-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Holder MK, Blaustein JD. Puberty and adolescence as a time of vulnerability to stressors that alter neurobehavioral processes. Front Neuroendocrinol 2014; 35(1):89-110. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.10.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Yang D, Li Y, Yuan J. The influence of pubertal development on adolescent depression: the mediating effects of negative physical self and interpersonal stress. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12:786386. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.786386 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Li D, Zhang J, Song G, Liu Q, Tang X. The relationship between parent-adolescent communication and depressive symptoms: the roles of school life experience, learning difficulties and confidence in the future. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2022; 15:1295-310. doi: 10.2147/prbm.S345009 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Huang XC, Zhang YN, Wu XY, Jiang Y, Cai H, Deng YQ. A cross-sectional study: family communication, anxiety, and depression in adolescents: the mediating role of family violence and problematic internet use. BMC Public Health 2023; 23(1):1747. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16637-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Melton TH, Croarkin PE, Strawn JR, McClintock SM. Comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a systematic review and analysis. J Psychiatr Pract 2016; 22(2):84-98. doi: 10.1097/pra.0000000000000132 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Llera SJ, Newman MG. Contrast avoidance predicts and mediates the effect of trait worry on problem-solving impairment. J Anxiety Disord 2023; 94:102674. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2023.102674 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiang MM, Gao K, Wu ZY, Guo PP. The influence of academic pressure on adolescents’ problem behavior: chain mediating effects of self-control, parent-child conflict, and subjective well-being. Front Psychol 2022; 13:954330. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.954330 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Steare T, Gutiérrez Muñoz C, Sullivan A, Lewis G. The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2023; 339:302-17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.028 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Wu J, Zhou Z, Tian Y, Li W, Xie H. Parent-adolescent discrepancies in educational expectations, relationship quality, and study engagement: a multi-informant study using response surface analysis. Front Psychol 2024; 15:1288644. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1288644 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Holder MK, Blaustein JD. Puberty and adolescence as a time of vulnerability to stressors that alter neurobehavioral processes. Front Neuroendocrinol 2014; 35(1):89-110. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.10.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Schlack R, Peerenboom N, Neuperdt L, Junker S, Beyer AK. The effects of mental health problems in childhood and adolescence in young adults: results of the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2021; 6(4):3-19. doi: 10.25646/8863 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sisk LM, Gee DG. Stress and adolescence: vulnerability and opportunity during a sensitive window of development. Curr Opin Psychol 2022; 44:286-92. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shah EN, Szwedo DE, Allen JP. Parental autonomy restricting behaviors during adolescence as predictors of dependency on parents in emerging adulthood. Emerg Adulthood 2023; 11(1):15-31. doi: 10.1177/21676968221121158 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bi X, Yang Y, Li H, Wang M, Zhang W, Deater-Deckard K. Parenting styles and parent-adolescent relationships: the mediating roles of behavioral autonomy and parental authority. Front Psychol 2018; 9:2187. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02187 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Fernandez CC, Hou Y, Gonzalez CS. Parent and teacher educational expectations and adolescents’ academic performance: mechanisms of influence. J Community Psychol 2021; 49(7):2679-703. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22644 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Boer H, Timmermans AC, van der Werf MP. The effects of teacher expectation interventions on teachers’ expectations and student achievement: narrative review and meta-analysis. Educ Res Eval 2018; 24(3-5):180-200. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2018.1550834 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Timmermans AC, de Boer H, van der Werf MP. An investigation of the relationship between teachers’ expectations and teachers’ perceptions of student attributes. Soc Psychol Educ 2016; 19(2):217-40. doi: 10.1007/s11218-015-9326-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther 1990; 28(6):487-95. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dehshiri G, Golzari M, Borjali A, Sohrabi F. Psychometrics particularity of Farsi version of Pennsylvania State Worry Questionnaire for college students. J Clin Psycol 2009; 1(4):67-75. doi: 10.22075/jcp.2017.1988.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ang RP, Huan VS. Academic expectations stress inventory: development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Educ Psychol Meas 2006; 66(3):522-39. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282461 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Habibi Asgarabad M, Charkhabi M, Fadaei Z, Baker JS, Dutheil F. Academic expectations of stress inventory: a psychometric evaluation of validity and reliability of the Persian version. J Pers Med 2021;11(11). 10.3390/jpm11111208.

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social Skills Rating System: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990.

- Eslami AA, Amidi Mazaheri M, Mostafavi F, Abbasi MH, Noroozi E. Farsi version of social skills rating system-secondary student form: cultural adaptation, reliability and construct validity. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci 2014; 8(2):97-104. [ Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Zhang Q, Ran G. The association between academic stress and test anxiety in college students: the mediating role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and the moderating role of parental expectations. Front Psychol 2023; 14:1008679. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1008679 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peleg O, Deutch C, Dan O. Test anxiety among female college students and its relation to perceived parental academic expectations and differentiation of self. Learn Individ Differ 2016; 49:428-36. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein L, Rubie-Davies CM, Brühwiler C. Teacher expectations and their relations with primary school students’ achievement, self-concept, and anxiety in mathematics. Soc Psychol Educ 2024; 27(2):567-86. doi: 10.1007/s11218-023-09856-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lai F, Wang L, Zhang J, Shan S, Chen J, Tian L. Relationship between social media use and social anxiety in college students: mediation effect of communication capacity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20(4):3657. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043657 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]