Res Dev Med Educ. 13:27.

doi: 10.34172/rdme.33248

Original Article

Perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion in medical students

Ali Pourramzani Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, 1

Kosar Mosa Yasori Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, 1

Sajjad Saadat Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, 2

Fatemeh Eslamdoust-Siahestalkhi Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Author information:

1Kavosh Cognitive Behavior Sciences and Addiction Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2Neuroscience Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

Abstract

Background:

The association between perceived stress and somatization symptoms is significant. Self-compassion is a valuable coping resource for dealing with negative life situations. We examined the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion in medical students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Methods:

This study was a descriptive correlational study, based on structural equation modeling (SEM) on the medical students of Guilan University of Medical Science in the academic year 2022-2023. Demographic questionnaires, Perceived Stress Scale, Somatic Symptom Scale-8, and Self-Compassion Scale were used. Independent t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey’s test, Pearson correlation, Mann-Whitney test, and Kruskal–Wallis test were used for analysis by SEM in LISREL and SPSS software.

Results:

Participants were 200 students with a mean±SD age of 23.46±2.06 years. The mean scores of perceived stress, somatic symptoms, and self-compassion in the sample were 29.90±8.52, 10.59±4.94, and 3±0.63, respectively. There was a significant positive association between perceived stress and somatic symptoms (r=0.299, P<0.001) and a negative association between somatic symptoms and self-compassion (r=-0.490, P<0.001), but no relationship between perceived stress and self-compassion (r=-0.124, P=0.081). The mediating role of self-compassion was confirmed by none of the modified models.

Conclusion:

Although increased perceived stress was related to increased somatic symptoms, and increased somatic symptoms were related to decreased self-compassion, self-compassion did not mediate the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms.

Keywords: Stress, Somatic symptoms, Self-compassion, Medical students

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the

original authors and source are cited. No permission is required from the authors or the publishers.

Funding Statement

This paper did not receive any funding from any institute or organization.

Introduction

Perceived stress is the individual’s feelings or thoughts about the amount of stress they experience at a given point in time or during a given time. Perceived stress includes feelings about the uncontrollable and unpredictable things in life, the number of times a person faces distressing problems, and confidence in their ability to cope with problems.1 Perceived stress is not the types or frequency of a person’s stressful events, but rather how a person deals with stressors in their life. Individuals may experience similar negative events, but their impact or intensity depends on factors such as personality, coping resources, and support.2

Stress in healthcare professionals has been one of the important problems.3-5 According to studies, mental health problems, including depression, stress, and burnout, are more common in medical students compared to their peers.6-9 This difference may be due to the higher workload, psychological tensions, and shift work in the workplace. One of the common mental health problems among medical students is psychosomatic symptoms, which previous studies have reported as high as 70%.10 In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), somatic symptom disorder (SSD) is characterized as the presence of one or more physical symptoms along with excessive thoughts, feelings, and/or behavior associated with the symptom that leads to intolerable distress and/or functional impairment.11 Some studies have shown that perceived stress and somatization symptoms are related.12-14

Self-compassion might be a valuable coping resource in negative life situations and plays an important role in the coping process. It can help people to cope with negative situations and not avoid challenging tasks for fear of failure.15 Self-compassion includes three main components, self-kindness/self-judgment, feelings of common humanity/isolation, and mindfulness/over-identification.16 Studies showed that self-compassion and perceived stress had a negative correlation,17-20 and self-compassion was known as a moderator of perceived stress.17,18 Also, self-compassion mediates the relationship between resilience and somatization,21 and people with a lower level of self-compassion had more physical symptoms.22,23 and the importance of the mental health of this group, it is necessary to conduct further investigation.

Considering the high prevalence of somatic symptoms and higher levels of stress among medical students in previous studies and its negative impact on people’s mental health, conducting studies in this field seems necessary. On the other hand, the role of self-compassion in increasing the level of resilience and coping process, examining its relationship with stress and somatic symptoms can lead to interesting results. It is important to promote mental health in medical students in our country, and no study has been conducted to investigate the relationship between perceived stress, somatic symptoms, and self-compassion in this group. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion in medical students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

Methods

This study was a descriptive correlational study that was carried out on structural equation modeling (SEM). The medical students of Guilan University of Medical Science in the academic year 2022-2023 were the sample population. For selecting participants, the convenience sampling method was used. Inclusion criteria were medical students who were studying at the Guilan University of Medical Sciences and cooperation to join in the study. The only exclusion criterion was an incomplete questionnaire. Before participating in the study, the purpose of the study was explained to the participants and the informed consent was signed by them.

Sample size

Considering the analysis of SEM and the number of latent variables in the used questionnaires, which was equal to 9, 20 samples were required for each latent variable. The minimum sample size was calculated at 180. According to the recommendation of a minimum sample size of 200 for SEM,24 a sample size of 200 was considered.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire: This questionnaire included age, gender, education level, marital status, grade point average (GPA), and history of medical and mental diseases.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS): This tool was made by Cohen et al,25 and is a 14-item scale for measuring stressful life situations. It has two subscales, the negative part (items, including 1, 2, 3, 8, 11, 12, and 14) and the positive part (items, including 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13). This scale is scored from 0 “never” to 4 “very often”, and the scoring of the positivity subscale is reversed. So, the total score is from 0-56, and higher scores indicate greater stress.26 In this study, similar to two previous studies,27,28 the score of 28 was considered as a cut-off value for stressed and no stressed. In the original research, the coefficient alpha reliability for the scale was 0.84-0.86.25 In the Persian version, all three forms of the PSS (PSS-14, PSS-10, and PSS-4) had a significant correlation with the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) which indicated an acceptable convergent validity.29 Also, the coefficient alpha reliability of the Persian version of PSS was 0.76.30

The Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8): This scale is a self-report questionnaire for measuring the burden of somatic symptoms, developed by Gierk et al.31 The total score for the scale is between 0 and 32 (0 “ not at all “- 4” very much “), and the score categories are no to minimum (scores: 0-3), low (scores: 4-7), moderate (scores: 8-11), high (scores: 12-15), and very high (scores: > 16) burden of somatic symptoms. The reliability was good (Cronbach α = 0.81).31 In the study by Goodarzi et al, the concurrent validity analysis of the Persian version of the SSS-8 scale indicated a significant correlation with other mental health scales, such as General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), and internal consistency reliability by Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75.32

Self-compassion scale: It is a 12-item scale, measuring self-compassion. This scale has six subscales, including self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. Scoring is from 1 “rarely” to 5 “almost always”. The mean of each of the subscales and the total mean are calculated, which is a number between 1 and 5. In scoring, a score of 1-2.5, 2.5-3.5, and 3.5-5 indicate low, moderate, and high levels of self-compassion, respectively. The test-retest reliability of the questionnaire was 0.92.33 In the Persian version, the correlation between scores of the self-compassion scale with other questionnaires, such as the external shame scale and perfectionism was significant, indicating appropriate divergent validity. Also, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total and three subscales (including self-kindness/self-judgment, common humanity/isolation, and mindfulness /over-identification) was 0.79, 0.68, 0.71, and 0.86, respectively.34

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was used by frequency (percentage) and mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for checking normality, and Levene’s test for checking the homogeneity of the variances. For inferential analysis, Pearson correlation, independent t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Tukey’s test were used, if the assumptions of parametric tests were not met, Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used. Also, data were analyzed using SEM in LISREL software version 8/80 and SPSS® version 24. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the present study, 200 medical students with a mean ± SD age (min-max) of 23.46 ± 2.06 (17-28) years participated. The mean ± SD GPA of subjects was 17.06 ± 1.11. The demographic characteristics of the participants are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of medical students (N = 200)

|

Variable

|

No. (%)

|

| Gender |

|

| Female |

103 (51.5%) |

| Male |

97 (48.5%) |

| Marital status |

|

| Single |

168 (84.0) |

| Married |

32 (16.0) |

| Education status |

|

| Basic sciences |

53 (26.5) |

| Physiopathology |

44 (22.0) |

| Externship |

57 (28.5) |

| Internship |

46 (23.0) |

| History of medical diseases |

|

| Yes |

20 (10.0) |

| History of psychiatric disorders |

|

| Yes |

10 (5.0) |

The mean score of perceived stress in the participants was 29.90 ± 8.52 (min-max: 10-48). The mean scores of negative subscales and positive subscales of PSS were 15.04 ± 4.57 (min-max: 3-23) and 14.86 ± 4.41 (min-max: 7-25), respectively. The mean score of somatic symptoms was 10.59 ± 4.94 (min-max: 1-25). Based on mild, moderate, severe, and very severe levels, 25.0%, 33.5%, 21.0%, and 17.0% had somatic symptoms, respectively. Also, only 3.5% of the subjects had no somatic symptoms. 112 students (56%) experienced levels of stress. The total mean of self-compassion was 3 ± 0.63. 25%, 43.5%, and 31.5% of participants had mild, moderate, and high self-compassion. The subscales’ mean of self-compassion was 3.09 ± 0.77 for self-kindness, 2.98 ± 0.76 for self-judgment, 3.02 ± 0.75 for common humanity, 2.86 ± 0.85 for isolation, 3.14 ± 0.75 for mindfulness, and 2.92 ± 0.85 for over-identification.

The mean score of perceived stress in terms of demographic characteristics is shown in Table 2. In terms of education level, the perceived stress score had a significant difference, and people with a history of psychiatric disorder had a significantly higher score in perceived stress compared to the group without a history of psychiatric disorder. According to the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient, the score of perceived stress and age had a significant negative correlation (r = -0.241, P = 0.001), and older participants had less perceived stress compared to younger ones.

Table 2.

The mean score of perceived stress in terms of demographic characteristics

|

Variable

|

Perceived stress score

(Mean±SD)

|

P

value

|

| Gender |

|

|

| Female |

29.04 ± 8.65 |

0.144a |

| Male |

30.81 ± 8.33 |

|

| Marital status |

|

|

| Single |

29.74 ± 8.61 |

0.542a |

| Married |

30.75 ± 8.14 |

|

| Education status |

|

|

| Basic sciences |

33.33 ± 8.25 |

0.004b |

| Physiopathology |

27.72 ± 7.50 |

|

| Externship |

29.61 ± 8.16 |

|

| Internship |

28.39 ± 9.21 |

|

| GPA |

|

|

| < 17 |

29.63 ± 8.35 |

0.594a |

| > 17 |

30.29 ± 8.81 |

|

| History of medical diseases |

|

|

| Yes |

31.50 ± 8.44 |

0.379a |

| No |

29.72 ± 8.54 |

|

| History of psychiatric disorders |

|

|

| Yes |

36.90 ± 4.01 |

0.004c |

| No |

29.53 ± 8.54 |

|

a Independent-samples t test; b Mann-Whitney U test; c One-way ANOVA.

Table 3 indicates the mean score of somatic symptoms in terms of demographic characteristics. The basic sciences and physiopathology groups of participants had significantly higher scores of somatic symptoms. Subjects with higher age had less somatic symptoms, but this relationship was not significant (r = -0.128, P = 0.072).

Table 3.

The mean score of somatic symptoms in terms of demographic characteristics

|

Variable

|

Somatic symptoms score

(Mean±SD)

|

P

value

|

| Gender |

|

|

| Female |

10.84 ± 5.01 |

0.463a |

| Male |

10.32 ± 4.87 |

|

| Marital status |

|

|

| Single |

10.34 ± 4.93 |

0.102a |

| Married |

11.90 ± 4.88 |

|

| Education status |

|

|

| Basic sciences |

10.88 ± 6.05 |

0.007b |

| Physiopathology |

12.84 ± 4.95 |

|

| Externship |

9.10 ± 3.65 |

|

| Internship |

9.95 ± 4.17 |

|

| GPA |

|

|

| < 17 |

10.37 ± 4.63 |

0.466a |

| > 17 |

10.91 ± 5.37 |

|

| History of medical diseases |

|

|

| Yes |

10.10 ± 5.19 |

0.638a |

| No |

10.65 ± 4.92 |

|

| History of psychiatric disorders |

|

|

| Yes |

9.70 ± 4.34 |

0.558a |

| No |

10.64 ± 4.97 |

|

a Independent-samples t-test; b Kruskal-Wallis test.

There was no significant difference between mean self-compassion scores in terms of demographic characteristics (Table 4). The score of self-compassion and age had no significant relationship (r = 0.024, P = 0.735).

Table 4.

The mean score of self-compassion in terms of demographic characteristics

|

Variable

|

Self-compassion score

Mean±SD

|

P

-value

|

| Gender |

|

|

| Female |

3.03 ± 0.64 |

0.478a |

| Male |

2.97 ± 0.62 |

|

| Marital status |

|

|

| Single |

2.97 ± 0.63 |

0.189a |

| Married |

3.14 ± 0.61 |

|

| Education status |

|

|

| Basic sciences |

3.01 ± 0.77 |

0.931b |

| Physiopathology |

3.02 ± 0.56 |

|

| Externship |

3.02 ± 0.61 |

|

| Internship |

2.95 ± 0.54 |

|

| GPA |

|

|

| < 17 |

2.95 ± 0.60 |

0.207a |

| > 17 |

3.07 ± 0.67 |

|

| History of medical diseases |

|

|

| Yes |

3.04 ± 0.62 |

0.788a |

| No |

3.00 ± 0.63 |

|

| History of psychiatric disorders |

|

|

| Yes |

2.90 ± 0.67 |

0.621a |

| No |

3.01 ± 0.63 |

|

a Independent-samples t-test, b Kruskal-Wallis test

Based on the Pearson correlation coefficient, perceived stress and somatic symptoms had a significant positive relationship (r = 0.299, P < 0.001). Also, somatic symptoms and self-compassion had a significant negative relationship (r = -0.490, P < 0.001), but no significant relationship was observed between perceived stress and self-compassion (r = -0.124, P = 0.081).

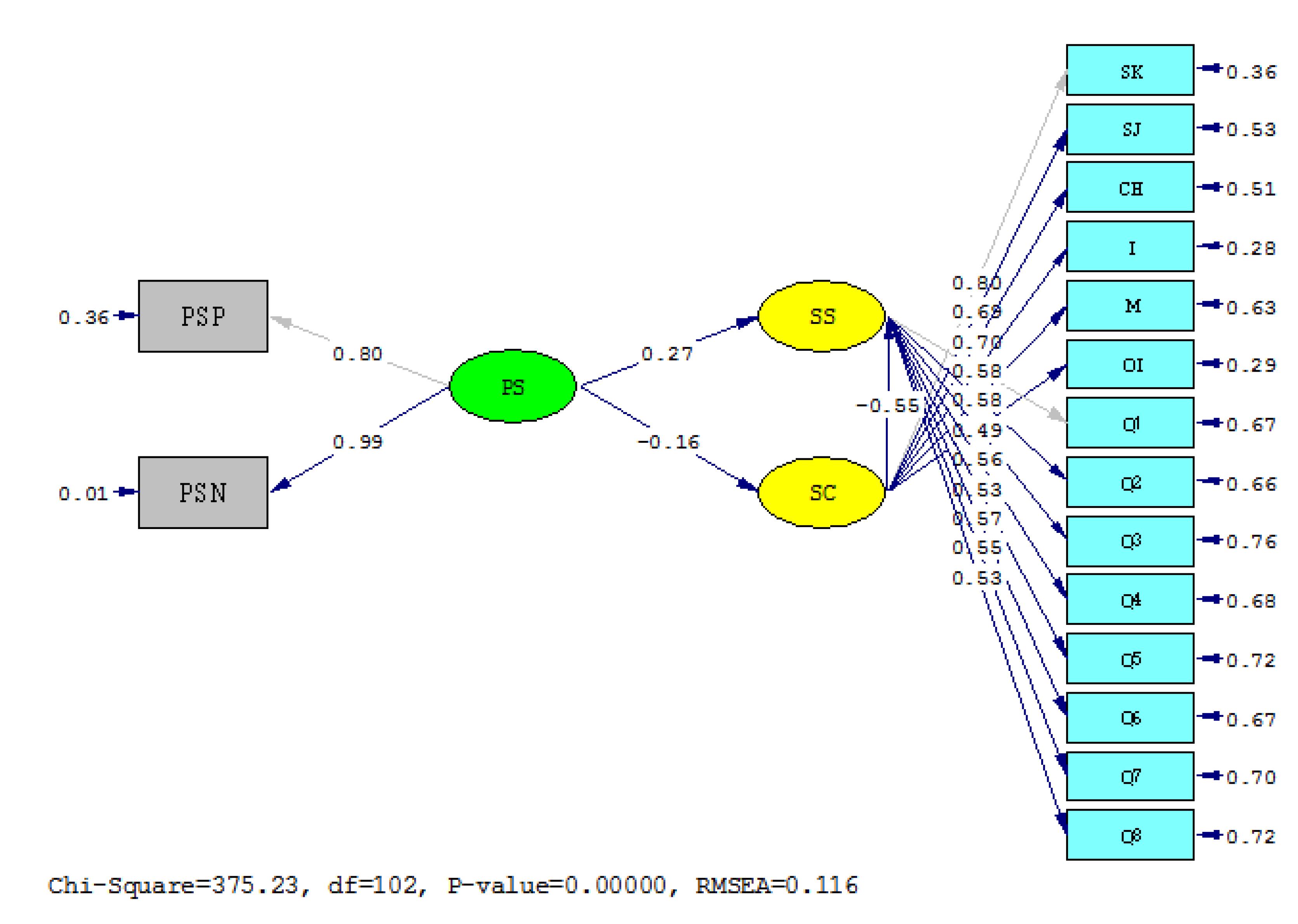

According to the model fit indicators (Table 5), the model presented in Figure 1 did not have a proper fit. Despite correlating the errors, none of the models had an acceptable fit.

Table 5.

Values of the model fit indicators

|

Fit indicators

|

ꭓ2

|

ꭓ2/df

|

P

|

RMSEA

|

GFI

|

AGFI

|

CFI

|

NFI

|

| Values |

375.23 |

3.67 |

< 0.001 |

0.12 |

0.81 |

0.75 |

0.90 |

0.87 |

Figure 1.

Structural equation model of the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion

PS: perceived stress, PSP: perceived stress positive domain, PSN: perceived stress negative domain, SS: somatization syndrome, SC: self-compassion, SK: self-kindness, SJ: self-judgment, CH: common humanity, I: isolation, M: mindfulness, OI: over-identification.

.

Structural equation model of the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion

PS: perceived stress, PSP: perceived stress positive domain, PSN: perceived stress negative domain, SS: somatization syndrome, SC: self-compassion, SK: self-kindness, SJ: self-judgment, CH: common humanity, I: isolation, M: mindfulness, OI: over-identification.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to survey the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion in medical students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. In the present study, perceived stress in medical students was significantly different based on their educational status. The perceived stress level of the participants was higher at the basic science level. As expected, people with a history of psychiatric disorder compared to the group without a history of psychiatric disorder had a significantly higher score in perceived stress. Also, the score of perceived stress and age had a significant negative relationship, and younger students had higher perceived stress.

In the study by Borjalilu et al,27 used PSS-14 for assessing perceived stress, 83% of medical students had levels of perceived stress (vs. 56% in this study), and the mean score of perceived stress was 32.02, which was slightly higher than our results. Wang et al35 found that 82% of medical students reported moderate to high stress. In a Saudi Arabia study in 2016, severe stress was reported around 34%.36 In a study in the United States, medical students had higher perceived stress, negative coping, and resilience than the general population.37 As expected, medical students experienced more stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the level of stress in our sample was less compared to similar studies, which may be due to different questionnaires and criteria to measure the level of perceived stress. Similar to our study, in the study by Wang et al35 and Saeed et al,36 junior students experienced more perceived stress than senior ones, but the results of Borjalilu et al27 were the opposite. Less qualified students might experience higher levels of stress due to lower levels of overall adjustment and maturity.5 Age may influence the experience of stress through the development of coping strategies, and older students use adaptive strategies, such as better planning ability.38 We also found no difference between men and women in stress. But in other studies,27,35,36 women experienced more stress. In two previous studies,27,35 the number of women was almost double that of men, whereas the number of women and men in our study was almost the same.

According to the present study, most of the participants had moderate somatic symptoms. Basic science and physiopathology groups had significantly higher somatic symptoms. So, the level of somatic symptoms was higher in junior students like perceived stress. In a study in Saudi Arabia,39 the rate of severe and very severe somatic symptoms in medical students was similar to ours (39% vs. 38%). However, the overall prevalence of somatic symptoms was much higher in our study. In a study in Mexico in 2020, the prevalence of somatization in medical students was 66.59%.40 In a recent review article, the prevalence of somatic symptoms in medical students was reported 5.7 to 80.1% (the mean of all percentages was 26.3%), and females had a higher frequency of mental health-related somatic symptoms.41 Also, in a study in Kazakhstan in 2018, the prevalence of somatic distress in medical students was 36.1%, and females had significantly more somatic distress than males.42 In public, the prevalence of somatic symptoms (in the level of moderate to severe) was less reported (15%).43 High prevalence of mental health problems in medical students9,44,45 might be due to stresses of daily life and extra stress caused by academic pressure, such as long periods of study, sleep deprivation, unhealthy work environments, and dealing with illnesses. In addition, according to evidence, the COVID-19 pandemic increased stress levels,46 thereby increasing the rate of mental health problems.

Among the students, 43.5% of them had moderate self-compassion, and 31.5% had high self-compassion. Similar to our study, Zhao et al47 found no significant difference in self-compassion scores in terms of demographic characteristics. However in the study by Godthelp et al,48 males and older participants had higher levels of self-compassion. In a study in Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students, the self-compassion of 29% of students was in the medium percentile and 32% in the medium-high and high percentile, and self-compassion had no significant differences in both genders similar to our study.49 Self-compassion may be an effective strategy to cope with stressors.37,50 In some studies,47,51 increasing self-compassion had a relationship with decreasing stress. However, the negative relationship between perceived stress and self-compassion was not significant in the present study.

Similar to our study, in other studies,12-14 perceived stress and somatic symptoms had a significant positive relationship. While a low level of stress can be a motivator, a high level of stress plays an important role in decreasing well-being.52 Thus, it can lead to health problems. Moreover, somatic symptoms and self-compassion had a negative relationship. Similar to our study, Sheikholeslami and Mohammadi found that teaching self-compassion to female heads of the household can reduce somatic symptoms in them.53 In another study, in people suffering from somatoform disorder, less self-compassion was associated with more somatic symptoms. So, self-compassion was suggested as a target in the treatment of individuals with somatoform disorders.22 While self-compassion as a coping strategy can help people to deal with negative situations and stressors, we could not find any significant relationship between perceived stress and self-compassion in participants.

In our study, the presented model was not acceptable for examining the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion. Several correction measures were performed, but none of the modified models had an acceptable fit. Feizollahi et al demonstrated a marginal role of self-compassion as a mediator in the relationship between perceived social support and psychosomatic symptoms.23 More research is needed to examine the relationship of perceived stress and somatic symptoms with the mediating role of self-compassion in medical students. Therefore, it is suggested to conduct more studies to investigate the exact relationship between them and their role in increasing the level of mental health of students, especially medical students.

Conclusion

Based on the study, students at the basic science level, with a history of psychiatric disorder, and at a younger age experienced higher levels of perceived stress. Also, somatic symptom scores were significantly higher in the basic sciences and physiopathology groups. However, self-compassion scores were not significantly different in terms of demographic characteristics. There was a significant positive association between perceived stress and somatic symptoms and a significant negative relationship between somatic symptoms and self-compassion. However, this relationship was not significant between perceived stress and self-compassion. The role of self-compassion as a mediator in the relationship between perceived stress and somatic symptoms was not confirmed.

Acknowledgments

The authors especially appreciate all the participants in this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The Ethical Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences approved this research (code: IR.GUMS.REC. 1401.187).

References

- Hampel P, Petermann F. Perceived stress, coping, and adjustment in adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2006; 38(4):409-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ng DM, Jeffery RW. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychol 2003; 22(6):638-42. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(18):1377-85. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mohanty A, Kabi A, Mohanty AP. Health problems in healthcare workers: a review. J Family Med Prim Care 2019; 8(8):2568-72. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_431_19 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pacheco JP, Giacomin HT, Tam WW, Ribeiro TB, Arab C, Bezerra IM. Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry 2017; 39(4):369-78. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nair M, Moss N, Bashir A, Garate D, Thomas D, Fu S. Mental health trends among medical students. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2023; 36(3):408-10. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2023.2187207 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson E. Medical students face high levels of mental health problems but stigma stops them getting help. BMJ 2023; 381:933. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p933 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rtbey G, Shumet S, Birhan B, Salelew E. Prevalence of mental distress and associated factors among medical students of University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2022; 22(1):523. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04174-w [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Collier R. Imagined illnesses can cause real problems for medical students. CMAJ 2008; 178(7):820. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080316 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kurlansik SL, Maffei MS. Somatic symptom disorder. Am Fam Physician 2016; 93(1):49-54. [ Google Scholar]

- Lim JW. The Impacts of Stress-Related Factors on Somatization Symptoms. Presented at: the SSWR Conference; 2006; San Antonio, Texas.

- Gandhi S, Sangeetha G, Ahmed N, Chaturvedi SK. Somatic symptoms, perceived stress and perceived job satisfaction among nurses working in an Indian psychiatric hospital. Asian J Psychiatr 2014; 12:77-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kadzikowska-Wrzosek R. Perceived stress, emotional ill-being and psychosomatic symptoms in high school students: the moderating effect of self-regulation competences. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 2012; 3:25-33. [ Google Scholar]

- Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2010; 4(2):107-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Neff K. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003; 2(2):85-101. doi: 10.1080/15298860309032 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bui TH, Nguyen TN, Pham HD, Tran CT, Ha TH. The mediating role of self-compassion between proactive coping and perceived stress among students. Sci Prog 2021; 104(2):368504211011872. doi: 10.1177/00368504211011872 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi A, Taheri A, Allen KA. Self-compassion moderates the perceived stress and self-care behaviors link in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2020; 29(5):927-33. doi: 10.1002/pon.5369 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stutts LA, Leary MR, Zeveney AS, Hufnagle AS. A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between self-compassion and the psychological effects of perceived stress. Self Identity 2018; 17(6):609-26. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1422537 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Meng R, Li J, Liu B, Cao X, Ge W. Self-compassion may reduce anxiety and depression in nursing students: a pathway through perceived stress. Public Health 2019; 174:1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.05.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shangguan F, Zhou C, Qian W, Zhang C, Liu Z, Zhang XY. A conditional process model to explain somatization during coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic: the interaction among resilience, perceived stress, and sex. Front Psychol 2021; 12:633433. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633433 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dewsaran-van der Ven C, van Broeckhuysen-Kloth S, Thorsell S, Scholten R, De Gucht V, Geenen R. Self-compassion in somatoform disorder. Psychiatry Res 2018; 262:34-9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.013 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Feizollahi Z, Asadzadeh H, Bakhtiarpour S, Farrokhi N. The mediating role of self-compassion in the correlation between perceived social support and psychosomatic symptoms among students with gender as the moderator. J Health Rep Technol 2022; 8(2):e119542. doi: 10.5812/ijhls.119542 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Publications; 2023.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24(4):385-96. [ Google Scholar]

- Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, Varvogli L, Gnardellis C, Chrousos GP. Perceived stress scale: reliability and validity study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011; 8(8):3287-98. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8083287 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Borjalilu S, Mohammadi A, Mojtahedzadeh R. Sources and severity of perceived stress among Iranian medical students. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2015; 17(10):e17767. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.17767 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Amr M, Hady El Gilany A, El-Hawary A. Does gender predict medical students’ stress in Mansoura, Egypt?. Med Educ Online 2008; 13:12. doi: 10.3885/meo.2008.Res00273 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Maroufizadeh S, Zareiyan A, Sigari N. Psychometric properties of the 14, 10 and 4-item “perceived stress scale” among asthmatic patients in Iran. Payesh 2014;13(4):457-65. [Persian].

- Safaei M, Shokri O. Assessing stress in cancer patients: factorial validity of the perceived stress scale in Iran. J Nurs Educ 2014;2(1):13-22. [Persian].

- Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Kroenke K, Spangenberg L, Zenger M, Brähler E. The somatic symptom scale-8 (SSS-8): a brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(3):399-407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi M, Ahmadi SM, Asle Zaker Lighvan M, Rahmati F, Molavi M, Mohammadi M. Investigating the psychometric properties of the 8-item somatic symptom scale in non-clinical sample of Iranian people. Pract Clin Psychol 2020; 8(1):57-64. doi: 10.32598/jpcp.8.1.59 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness 2016; 7(1):264-74. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Khanjani S, Foroughi AA, Sadghi K, Bahrainian SA. Psychometric properties of Iranian version of self-compassionscale (short form). Pajoohandeh Journal 2016;21(5):282-9. [Persian].

- Wang J, Liu W, Zhang Y, Xie S, Yang B. Perceived stress among Chinese medical students engaging in online learning in light of COVID-19. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2021; 14:549-62. doi: 10.2147/prbm.S308497 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Saeed AA, Bahnassy AA, Al-Hamdan NA, Almudhaibery FS, Alyahya AZ. Perceived stress and associated factors among medical students. J Family Community Med 2016; 23(3):166-71. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.189132 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rahimi B, Baetz M, Bowen R, Balbuena L. Resilience, stress, and coping among Canadian medical students. Can Med Educ J 2014; 5(1):e5-12. [ Google Scholar]

- Neufeld A, Malin G. How medical students cope with stress: a cross-sectional look at strategies and their sociodemographic antecedents. BMC Med Educ 2021; 21(1):299. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02734-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Goweda R, Alshinawi M, Janbi B, Idrees U, Babukur R, Alhazmi H. Somatic symptom disorder among medical students in Umm Al-Qura university, Makkah Al-Mukarramah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Middle East J Fam. Med 2022; 20(5):6-11. doi: 10.5742/mewfm.2022.9525030 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Brambila-Tapia AJL, Meda-Lara RM, Palomera-Chávez A, de-Santos-Ávila F, Hernández-Rivas MI, Bórquez-Hernández P. Association between personal, medical and positive psychological variables with somatization in university health sciences students. Psychol Health Med 2020; 25(7):879-86. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1683869 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sperling EL, Hulett JM, Sherwin LB, Thompson S, Bettencourt BA. Prevalence, characteristics and measurement of somatic symptoms related to mental health in medical students: a scoping review. Ann Med 2023; 55(2):2242781. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2023.2242781 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ibrayeva Z, Aldyngurov D, Myssayev A, Meirmanov S, Zhanaspayev M, Khismetova Z. Depression, anxiety and somatic distress in domestic and international undergraduate medical students in Kazakhstan. Iran J Public Health 2018; 47(6):919-21. [ Google Scholar]

- Hinz A, Ernst J, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, Rauscher FG, Petrowski K. Frequency of somatic symptoms in the general population: normative values for the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15). J Psychosom Res 2017; 96:27-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.12.017 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chau SW, Lewis T, Ng R, Chen JY, Farrell SM, Molodynski A. Wellbeing and mental health amongst medical students from Hong Kong. Int Rev Psychiatry 2019; 31(7-8):626-9. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2019.1679976 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi T, Ansari T, Alfahaid F, Alzaharani M, Almansour M, Sami W. Prevalence of mental distress among undergraduate medical students at Majmaah university, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Majmaah J Health Sci 2017; 5(2):66-75. doi: 10.5455/mjhs.2017.02.008 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Broks VM, Stegers-Jager KM, van der Waal J, van den Broek WW, Woltman AM. Medical students’ crisis-induced stress and the association with social support. PLoS One 2022; 17(12):e0278577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278577 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhao FF, Yang L, Ma JP, Qin ZJ. Path analysis of the association between self-compassion and depressive symptoms among nursing and medical students: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs 2022; 21(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00835-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Godthelp J, Muntinga M, Niessen T, Leguit P, Abma T. Self-care of caregivers: self-compassion in a population of Dutch medical students and residents. MedEdPublish (2016) 2020; 9:222. doi: 10.15694/mep.2020.000222.1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- de Franco Tobar C, Michels M, Franco SC. Self-compassion and positive and negative affects on medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hum Growth Dev 2022; 32(2):339-50. doi: 10.36311/jhgd.v32.11909 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Román-Calderón JP, Krikorian A, Ruiz E, Romero AM, Lemos M. Compassion and self-compassion: counterfactors of burnout in medical students and physicians. Psychol Rep 2024; 127(3):1032-49. doi: 10.1177/00332941221132995 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Meng R, Luo X, Du S, Luo Y, Liu D, Chen J. The mediating role of perceived stress in associations between self-compassion and anxiety and depression: further evidence from Chinese medical workers. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2020; 13:2729-41. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.S261489 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Garfin DR, Thompson RR, Holman EA. Acute stress and subsequent health outcomes: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2018; 112:107-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.05.017 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sheikholeslami A, Mohammadi N. The effect of cognitive self-compassion on mental health (somatization, anxiety, social dysfunction, depression) of woman headed households. Journal of Counseling Research 2019; 18(70):83-104. doi: 10.29252/jcr.18.70.83.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]