Res Dev Med Educ. 13:15.

doi: 10.34172/rdme.33214

Original Article

The association between family emotional climate and moral development with vandalism in students: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy

Pakzad Sadeghi Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft,

Fatemeh Sadat Marashian Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, *

Alireza Heidari Software,

Author information:

Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran

Abstract

Background:

Research on the mediating role of academic self-efficacy can help identify how the family environment and moral judgment influence destructive behaviors, informing targeted strategies to promote positive youth development. This study investigates the mediating role of academic self-efficacy in the relationship between family emotional climate and moral development with vandalism in students.

Methods:

In this research, a correlational path analysis framework was adopted to investigate the relationships between various factors and destructive behaviors in adolescents. The target population encompassed all high school students within Eyvan, Iran, during the year 2023. A multistage cluster sampling approach yielded a sample of 364 participants. Standardized instruments assessed vandalism, family emotional climate, moral development, and academic self-efficacy. Structural equation modeling (SEM) software (AMOS 23) was utilized to evaluate the hypothesized model.

Results:

The findings revealed a non-significant direct association between family emotional climate and vandalism. In contrast, the analysis yielded significant positive and negative associations, respectively, between moral development and academic self-efficacy (P=0.001) and moral development and vandalism (P=0.001). The indirect effect of family emotional climate on vandalism through academic self-efficacy was negative and significant (P=0.012). Similarly, the indirect effect of moral development on vandalism mediated by academic self-efficacy was also negative and significant (P=0.009).

Conclusion:

These findings highlight the importance of promoting academic self-efficacy alongside efforts to cultivate positive family environments and moral development. By strengthening students’ belief in their academic abilities, interventions can empower them to make positive choices and reduce their likelihood of engaging in destructive behaviors like vandalism.

Keywords: Vandalism, Academic self-efficacy, Emotions, Moral development, Students

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Author(s).

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, as long as the

original authors and source are cited. No permission is required from the authors or the publishers.

Funding Statement

This paper did not receive any funding from any institute or organization.

Introduction

Behavioral problems are among the most prevalent challenges faced by students today. Adolescence is characterized by intense emotions, conflicting feelings, physiological arousal, and emotional turmoil.1 This period is marked by profound biological, psychological, and social changes that disrupt the physical and psychological equilibrium, leading to its characterization as a crisis of identity.2 Adolescence is a stage of life when behavioral inconsistencies are most prevalent, and one such inconsistency is the inclination toward risky behaviors.3 These behavioral issues are a major concern for families, parents, educators, and authorities. The growing prevalence of these behavioral problems negatively impacts individuals’ personal and social lives in adulthood and disrupts social tranquility and security.4,5

Student behavioral problems can be categorized into two main types: internal and external behavioral issues. Internal behavioral problems encompass conditions such as depression and anxiety. External behavioral problems involve those that affect an individual’s interactions with others.6 Vandalism falls within this category of issues.7 According to socio-cognitive perspectives, severe behavioral problems like vandalism are influenced by environmental factors.8 In most theories and models proposed to explain behaviors, the home and school are considered two of the most influential environments shaping individual behavior.9 Adolescent vandalism is one of the most critical issues that parents must address during puberty and take necessary steps to prevent it.10

The family serves as the primary social context in which children experience their formative years, acquiring fundamental life principles, essential life skills, and moral frameworks.11 Kapetanovic and Skoog12 define family emotional climate as the aggregate of emotional relationships and interactions, including the expression of emotions and interests, communication patterns, and interpersonal treatment among family members. Deficiencies in emotional dimensions, such as care, availability, and affection, can effectively predict a range of behavioral and academic problems during childhood and adolescence.13 The significance of the family lies in its role as a conduit for transmitting traits, beliefs, values, and cognitive frameworks. Children take their first steps towards socialization within the family, shaping their identity as social beings. Family members are influenced by the family’s emotional climate, adopting it as a model for their behavior.14

Within the family, children develop their initial perceptions of the world. They undergo physical and emotional growth, learn communication skills, internalize fundamental behavioral norms, and ultimately form their attitudes, ethics, and temperament, becoming socialized individuals.15 Research exploring parental interactions with children and parenting approaches highlights the enduring impact of parenting styles on individuals’ future behavior, expectations, and ultimately, their personality.16 Parents who restrict children’s self-expression or emotional disclosure hinder the development of their inner emotions and feelings, potentially leading to psychological distress, anxiety, and emotional turmoil in adulthood.17 Parenting practices and family emotional climate constitute the most critical and influential elements of the family in a child’s upbringing and emotional development.18

In the psychoanalytic framework, morality is equated with the superego or conscience, representing the internalized sense of guilt for transgressing moral principles and serving as a restraining force. Moral development entails the regulation of an individual’s relationship with themselves, nature, and their fellow human beings.19 Given the inherent connection between the foundations of morality and ethical judgment with concepts such as justice, altruism, respect for the rights of others, and adherence to laws, the positive impact of moral development on societal well-being is undeniable. Moral development plays a crucial role in shaping students’ character and behavior, influencing their interactions with others, their decision-making processes, and their overall contribution to society. Moral development encourages students to engage in prosocial behaviors, such as cooperation, empathy, and respect for others, while discouraging antisocial behaviors such as aggression, bullying, and vandalism.20 As students develop their moral understanding, they become more aware of their responsibilities and obligations as members of society. This heightened sense of responsibility promotes civic engagement and contributes to a more just and equitable society.21 Moral development equips students with the cognitive and emotional tools necessary to make ethical decisions in complex situations. They learn to consider the consequences of their actions, weigh different perspectives, and act following their moral values.22 A school environment characterized by strong moral values fosters a sense of respect, mutual understanding, and shared responsibility among students and staff. This positive climate promotes academic achievement, reduces conflict, and enhances overall well-being.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to achieve success in specific situations. At the core of self-efficacy lies the motivation to pursue positive goals and overcome obstacles that arise.23 Individuals with high levels of self-efficacy perceive themselves as having control over their lives and the power to influence circumstances through their actions and decisions. Conversely, those with low self-efficacy experience feelings of helplessness and a sense of inability to control events.24 Academic self-efficacy, a specific facet of self-efficacy, plays a pivotal role in students’ academic success and overall well-being. It encompasses a student’s belief in their ability to learn, perform, and achieve in academic settings.25

Students with high academic self-efficacy are more likely to be motivated to engage in learning activities, persist in the face of challenges, and set ambitious academic goals.26 Research consistently demonstrates a positive correlation between academic self-efficacy and student achievement.27 Students who believe in their abilities are more likely to succeed in their studies and attain higher academic outcomes. A strong sense of academic self-efficacy contributes to students’ overall mental health and well-being. Students who believe in their academic abilities are less likely to experience anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges.28

Vandalism is a prevalent problem among adolescents, causing significant social and economic costs. Understanding the factors that contribute to this destructive behavior is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. While previous research has explored the relationships between some of these factors individually, a gap exists in comprehensively examining their combined influence on vandalism. By addressing this knowledge gap, this study can provide valuable insights for educators, policymakers, and mental health professionals aiming to create a positive school environment, promote ethical decision-making, and foster student success, ultimately reducing destructive behaviors like vandalism. Therefore, according to the background of the research the present study aimed to investigate the mediating role of academic self-efficacy in the relationship between family emotional climate and moral development with vandalism in students.

Methods

This study employed a correlational path analysis design to explore the hypothesized relationships between anger rumination, physical health, and distress tolerance in a sample of male adolescents. The target population included all high school students (males and females) residing within Eyvan city during the academic year 2022-2023 (N = approximately 4445). A multi-stage cluster sampling technique was implemented to obtain a representative sample. In the first stage, five middle schools were randomly selected from the city’s geographically diverse pool of 20 schools. Stratification by geographic location within the city could be considered to further enhance representativeness if relevant to the research question. In the second stage, three classes were randomly chosen from each of the selected schools. Inclusion criteria for participation were: enrollment as a student in a participating middle school during the 2022-2023 academic year, physical attendance at school on the day of data collection, demonstrated comprehension of the questionnaires as assessed by a brief screening tool, and voluntary participation after receiving a thorough explanation of the research procedures and providing informed assent. Exclusion criteria included diagnosed cognitive impairments or learning disabilities documented in school records, incomplete questionnaires with a significant number of missing data points (defined as > 20% of total items), and responses with inconsistent or implausible patterns identified during data cleaning.

Instruments

Destructive Behaviors Propensity Questionnaire (DBPQ): The propensity for engaging in destructive behaviors (vandalism) within a school environment was measured using the DBPQ developed by Thawabieh and Al-rofo.29 This 18-item instrument utilizes a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to assess respondents’ level of agreement with each statement. Higher scores on the DBPQ indicate a greater tendency towards destructive behaviors in school. The instrument’s internal consistency reliability in the current investigation was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, resulting in a coefficient of 0.89. Saeedi et al30 established the questionnaire’s validity (CVI = 0.91, CVR = 0.89) and reported a comparable reliability coefficient of 0.94 for the DBPQ in their study.

Family Emotional Climate Questionnaire (FECQ): The FECQ by Hill Burn was utilized to assess the family environment. This instrument consists of 16 items divided into eight subscales (love, caress, affirmation, shared experiences, gift-giving, encouragement, trust, and sense of security), with two items per subscale. Respondents rate their level of agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high), reflecting their inner perceptions of the family environment. The Findings of FECQ demonstrated good internal consistency reliability in prior research, with Yousefi and Pariyad31 reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94. Additionally, the authors31 established its validity (CVI = 0.88, CVR = 0.86). In the present study, the FECQ yielded an acceptable reliability coefficient of 0.87.

Moral Development Scale (MDS): The MDS, developed by Manavipour,32 is a self-report instrument designed to assess individuals’ moral development across four distinct stages: pre-conventional morality, conventional morality, post-conventional morality, and prosocial morality. Comprising 13 items, the MDS utilizes a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to gauge participants’ level of agreement with each statement. Items 5, 6, 11, and 12 are reverse-coded to ensure a comprehensive assessment of moral reasoning. Manavipour32 conducted a thorough psychometric evaluation of the MDS, establishing its reliability and validity. The scale demonstrated strong internal consistency reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.93 in a sample of high school students. This finding indicates that the items within the MDS measure a unified concept of moral development.

Academic Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (ASEQ): The ASEQ by Jinks and Morgan33 was employed to evaluate students’ beliefs regarding their academic capabilities. This 30-item instrument comprises three subscales: talent (perceived natural ability), effort (belief in the impact of hard work), and texture (confidence in managing academic challenges). Utilizing a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree), the ASEQ assesses respondents’ level of agreement with each statement. Existing research supports the instrument’s internal consistency and reliability. Jinks and Morgan33 reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82, and Hosseinkhani et al34 obtained a similar value of 0.74. Furthermore, the authors34 established the instrument’s validity (CVI = 0.98, CVR = 0.96). In the current study, the ASEQ demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.82.

Data analysis

Bivariate correlations were employed to assess the linear relationships between the study variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient served as the primary measure of association. To examine the hypothesized model and its fit to the data, structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized. Software packages such as SPSS and AMOS v.23 facilitated the SEM analysis. This approach allowed for the simultaneous evaluation of both direct and indirect effects among the study variables within a single, comprehensive framework.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the study variables. Means and standard deviations (SD) are presented for family emotional climate (M = 43.72, SD = 12.68), moral development (M = 36.32, SD = 8.89), academic self-efficacy (M = 82.40, SD = 20.79), and vandalism (M = 39.07, SD = 15.54). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed normality for all variables, ensuring the suitability of parametric statistical methods for subsequent analyses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the studied variables

|

Variables

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Kolmogorov-Smirnov

|

|

Z

|

P

|

| Family emotional climate |

43.72 |

12.68 |

0.13 |

0.102 |

| Moral development |

36.32 |

8.89 |

0.05 |

0.200 |

| Academic self-efficacy |

82.40 |

20.79 |

0.06 |

0.190 |

| Vandalism |

39.07 |

15.54 |

0.06 |

0.190 |

Table 2 summarizes the Pearson correlation coefficients computed to examine the relationships between the study variables in the student sample. Family emotional climate displayed statistically significant positive correlations with both moral development (r = 0.34, P < 0.001) and academic self-efficacy (r = 0.64, P < 0.001). Conversely, a negative correlation emerged between family emotional climate and vandalism (r = -0.42, P < 0.001). Similarly, moral development exhibited a positive correlation with academic self-efficacy (r = 0.50, P < 0.001) but a negative correlation with vandalism (r = -0.70, P < 0.001). Finally, academic self-efficacy demonstrated a negative correlation with vandalism (r = -0.61, P < 0.001). These findings suggest potential interrelationships among the investigated variables, warranting further exploration through SEM to elucidate the direction and strength of these relationships.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficient of the studied variables

|

Variables

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

| 1- Family emotional climate |

1 |

0.34* |

0.64** |

-0.42** |

| 2- Moral development |

- |

1 |

0.50** |

-0.70** |

| 3- Academic self-efficacy |

- |

- |

1 |

-0.61** |

| 4- Vandalism |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

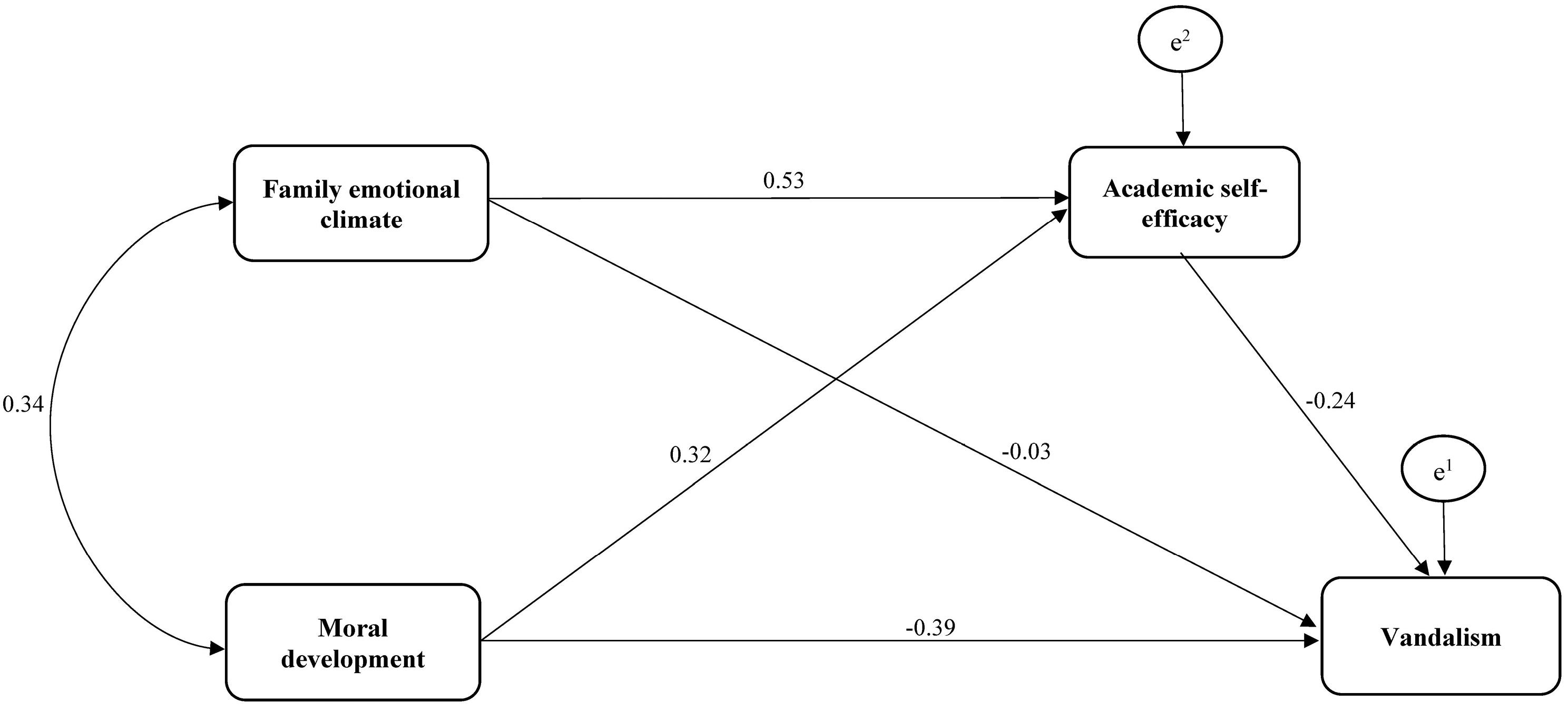

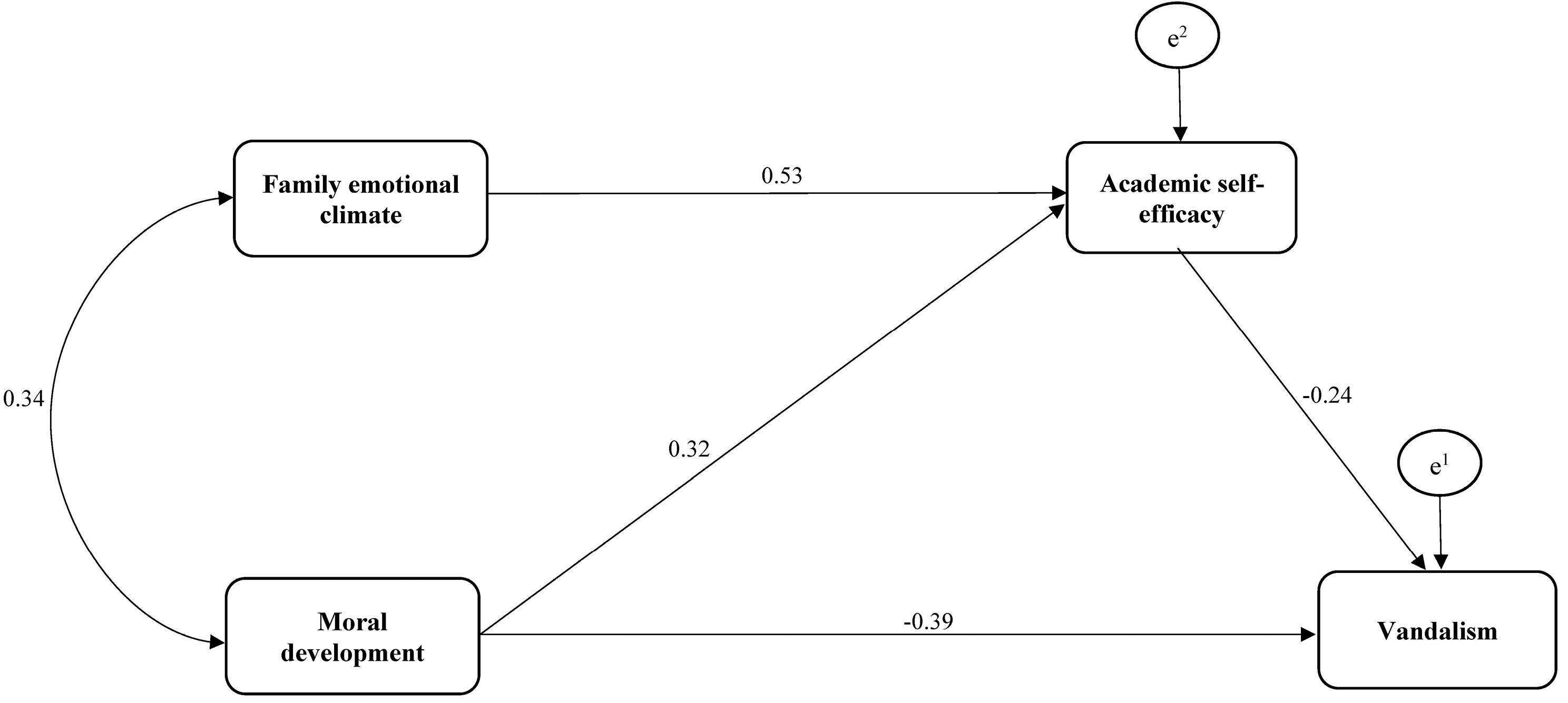

SEM was employed to evaluate the hypothesized model. While initial fit indices indicated a promising overall model fit, the path coefficient linking family emotional climate directly to student vandalism was not statistically significant. To address this lack of significance, a modification was made to the model by removing this non-significant path. Subsequently, the fit indices were reevaluated. Figures 1 and 2 depict the initial and final research models, respectively, along with their corresponding path coefficients.

Figure 1.

Initial research model with standardized path coefficients

.

Initial research model with standardized path coefficients

Figure 2.

Final research model with standardized path coefficients

.

Final research model with standardized path coefficients

Table 3 presents fit indices for the initial and final SEM models. All indices (χ2 = 1.60, χ2/df = 0.80, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.014) suggest a well-fitting final model (all ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08). This indicates the model adequately captures relationships between the study variables.

Table 3.

Fit indices for the proposed and final models

|

Fit indicators

|

χ2

|

df

|

(χ2/df)

|

GFI

|

AGFI

|

IFI

|

TLI

|

CFI

|

NFI

|

RMSEA

|

| Initial model |

16.60 |

1 |

16.60 |

0.98 |

0.73 |

0.98 |

0.81 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

0.210 |

| Final model |

1.60 |

2 |

0.80 |

0.99 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.95 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.014 |

GFI: Goodness of Fit Index; AGFI: Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; IFI: Incremental Fit Index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI: Comparative Fit Index; NFI: Normed Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Examination of path coefficients in Table 4 revealed significant positive direct effects of both family emotional climate and moral development on academic self-efficacy (P = 0.001). However, the direct influence of family emotional climate on vandalism was not statistically significant. Interestingly, both family emotional climate and moral development demonstrated significant indirect effects on vandalism with academic self-efficacy acting as a mediator (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Standard path coefficient related to direct and indirect relationships in the final model

|

Paths

|

β

|

P

|

| Family emotional climate → Academic self-efficacy |

0.53 |

0.001 |

| Family emotional climate → Vandalism |

-0.03 |

0.940 |

| Moral development → Academic self-efficacy |

0.32 |

0.001 |

| Moral development → Vandalism |

-0.39 |

0.001 |

| Academic self-efficacy → Academic self-efficacy |

-0.24 |

0.001 |

| Family emotional climate → Vandalism through academic self-efficacy |

-0.18 |

0.012 |

| Moral development → Vandalism through academic self-efficacy |

-0.11 |

0.009 |

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of academic self-efficacy in the relationship between family emotional climate and moral development with vandalism in students. Our analysis revealed significant direct positive effects of both family emotional climate and moral development on academic self-efficacy. Interestingly, while a direct association between family emotional climate and vandalism was absent, both factors exerted significant indirect effects on vandalism mediated by academic self-efficacy. This suggests that a positive family environment, while not directly impacting vandalism, can indirectly reduce it by fostering academic self-efficacy. Similarly, moral development’s positive effect on self-efficacy translates to a reduced likelihood of vandalism. The findings of this study align with those of Keshtvarz Kondazi and Fooladchang,35 Yousefi and Pariyad,31 and Modabber et al.36

Positive parental involvement with children and adolescents has demonstrably positive effects on various aspects of their lives, including academic success. Research suggests an inverse correlation between parental involvement and youth delinquency.3 Parental control and supervision are considered the most crucial mechanisms influenced by family relationships that shape child behavior. In other words, the social behaviors and actions of adolescents are significantly impacted by the quality of family care and supervision they receive.3

When parents effectively address their children’s emotional needs and tailor their interactions to each developmental stage, demonstrating an understanding of educational principles and personality development, children are more likely to exhibit academic self-efficacy.24 Fulfilling children’s basic needs within the family environment, particularly by parents, is considered a necessary condition for fostering attention, motivation, and enthusiasm for learning, all of which contribute to academic self-efficacy.24 Conversely, unmet or inadequately met physiological and psychological needs, such as security, love, and respect, can lead to anxiety and insecurity in school settings. Children experiencing such needs may become preoccupied with these concerns rather than focusing on problem-solving and engaging with cognitive tasks in the classroom. This insecure and potentially threatening environment can hinder learning. Therefore, it can be argued that many child development and educational challenges stem from the emotional atmosphere within the family. Efforts to support and educate parents can play a crucial role in addressing these challenges.12

The family environment plays a critical role in shaping adolescent behavior, particularly regarding emotional development. Early experiences within the family serve as the foundation for emotional regulation and social interaction skills.5 When families consistently fail to meet the material and psychological needs of adolescents, and parent-child relationships lack closeness and intimacy, the occurrence of risky behaviors becomes a more predictable consequence. Conversely, a strong and supportive parent-child relationship acts as a protective factor against these behaviors. Unfavorable family emotional atmospheres and experiences such as divorce are recognized as significant risk factors for adolescent vandalism.5 In essence, the emotional climate within the family and the quality of parent-child interactions are considered some of the most influential factors shaping children’s behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes. Warm, supportive, and nurturing family relationships, when not overly intrusive, can effectively deter adolescents from engaging in risky behaviors. These positive family dynamics fulfill the emotional needs of family members, strengthening the internal family system and fostering attachment and a sense of belonging.12

Research suggests a complex interplay between moral development and cognitive growth in students.19 As students’ intellectual abilities mature, their moral reasoning appears to develop alongside it. This suggests that students with higher academic self-efficacy may engage more critically with the ethical concepts embedded within their academic coursework, potentially fostering their moral development. Consequently, academic performance may hold some predictive power for moral development.19 Moral development can be understood as the internalization of social norms and regulations that guide prosocial behavior.22 As individuals progress through this developmental process, they demonstrate an increasing capacity to adhere to these norms and regulations. The text also touches on the concept of student motivation in the school setting. Students motivated by positive reinforcement or the avoidance of punishment tend to exhibit higher levels of academic self-efficacy and are less likely to experience academic decline.

Advanced moral development entails an individual’s ability to grasp the rational underpinnings of respecting others, telling the truth, engaging in virtuous behavior, and refraining from violence. Attaining this level of moral development, characterized by duty-based values and personal commitments like responsibility, fosters a sense of accountability for one’s choices. This internalized sense of responsibility leads to greater ethical scrutiny and sensitivity in one’s actions and decisions. Individuals who have experienced positive moral development through the influence of their school and parents are less likely to experience psychological distress.20 Consequently, their emotional well-being has a positive impact on their physical strength, laying the groundwork for the cultivation of willpower and perseverance.

Adolescence and young adulthood are marked by increased vulnerability to risky behaviors. However, research suggests that fostering self-efficacy in this population can serve as a protective factor.23 Education that cultivates self-efficacy empowers young individuals to develop robust problem-solving skills, potentially reducing their exposure to harmful behaviors and risk factors that can compromise well-being.23 Academic self-efficacy plays a critical role in regulating stress responses triggered by challenging situations. Individuals with high academic self-efficacy demonstrate superior stress management abilities, even under pressure, while those with low self-efficacy experience heightened anxiety in the face of academic challenges.26 Mounting evidence suggests that strong academic self-efficacy beliefs act as a buffer against the negative effects of psychological stressors and may even enhance immune system functioning.

The present study extends this line of inquiry by examining the indirect influence of family emotional climate and moral development on student vandalism through the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Supportive family environments and a sense of school value, fostered during the educational process, can instill a sense of competence in students. This, in turn, leads to greater academic engagement and success, potentially reducing the likelihood of engaging in destructive behaviors like vandalism. Individuals who perceive themselves as incapable and ineffective in academic pursuits are more susceptible to feelings of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness. Conversely, research consistently demonstrates a positive association between self-efficacy and psychological well-being.37

The study employed a correlational design, which can only establish relationships between variables but cannot determine causality. The study relied on self-reported measures of vandalism, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias (students under-reporting vandalism) or memory limitations. The sample consisted of male adolescents from Eyvan city. The findings may not generalize to other populations (e.g., female students, different age groups, or students from other geographical locations).

Conclusion

While a direct association between family emotional climate and vandalism was not observed, the findings revealed a more nuanced picture. Moral development emerged as a significant factor influencing both academic self-efficacy and vandalism. Students with higher moral development demonstrated greater belief in their academic capabilities and displayed lower levels of vandalism. Interestingly, academic self-efficacy played a crucial mediating role. The negative indirect effects of family emotional climate and moral development on vandalism were both mediated by academic self-efficacy. This suggests that fostering academic self-efficacy can act as a protective factor against vandalism, even in the context of less positive family environments or lower levels of initial moral development. These findings hold significant implications for future research, policy development, and interventions aimed at addressing vandalism prevention among students. Future research should delve deeper into the specific mechanisms by which academic self-efficacy influences vandalism. This could involve investigating the role of self-control, decision-making processes, and perceptions of academic success in influencing student behavior. Policymakers can leverage these findings to develop programs that promote academic self-efficacy alongside traditional approaches focused on improving family environments and moral development. This could include initiatives that enhance student engagement in learning, provide opportunities for academic achievement, and promote positive teacher-student relationships. School-based interventions can be tailored to target academic self-efficacy as a means of reducing vandalism. Such interventions might involve setting achievable academic goals, providing academic support programs, and fostering mastery experiences to build student confidence in their abilities. Overall, by strengthening students’ belief in their academic abilities, interventions can empower them to make positive choices and reduce their likelihood of engaging in destructive behaviors like vandalism.

Acknowledgments

This article was extracted from a part of the PhD dissertation of Mr. Pakzad Sadeghi in the Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. The researchers wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Islamic Azad University- Ahvaz Branch (code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1402.016).

References

- Peterle CF, Fonseca CL, de Freitas BH, Gaíva MA, Diogo PM, Bortolini J. Emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents in the context of COVID-19: a mixed method study. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2022; 30(spe):e3744. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.6273.3744 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore SJ. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020; 4(8):634-40. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(20)30186-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Povey J, Plage S, Huang Y, Gramotnev A, Cook S, Austerberry S, et al. Adolescence a period of vulnerability and risk for adverse outcomes across the life course: the role of parent engagement in learning. In: Baxter J, Lam J, Povey J, Lee R, Zubrick SR, eds. Family Dynamics over the Life Course: Foundations, Turning Points and Outcomes. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 97-131. 10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_6.

- Ge M, Yang M, Sheng X, Zhang L, Zhang K, Zhou R. Left-behind experience and behavior problems among adolescents: multiple mediating effects of social support and sleep quality. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2022; 15:3599-608. doi: 10.2147/prbm.s385031 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jogdand SS, Naik J. Study of family factors in association with behavior problems amongst children of 6-18 years age group. Int J Appl Basic Med Res 2014; 4(2):86-9. doi: 10.4103/2229-516x.136783 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ogundele MO. Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: a brief overview for paediatricians. World J Clin Pediatr 2018; 7(1):9-26. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v7.i1.9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Krieger H, DiBello AM, Neighbors C. An introduction to body vandalism: what is it? Who does it? When does it happen?. Addict Behav 2017; 64:89-92. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Younan D, Tuvblad C, Li L, Wu J, Lurmann F, Franklin M. Environmental determinants of aggression in adolescents: role of urban neighborhood greenspace. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016; 55(7):591-601. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev 2015; 9(3):323-44. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh C. Healthy adolescent development and the juvenile justice system: challenges and solutions. Child Dev Perspect 2022; 16(3):141-7. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12461 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Beigzadeh A, Rahimi M, Nazarieh M. Social family models: a way to foster social skills and learning. Res Dev Med Educ 2016; 5(1):1-2. doi: 10.15171/rdme.2016.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Skoog T. The role of the family’s emotional climate in the links between parent-adolescent communication and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 2021; 49(2):141-54. doi: 10.1007/s10802-020-00705-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiang MM, Gao K, Wu ZY, Guo PP. The influence of academic pressure on adolescents’ problem behavior: chain mediating effects of self-control, parent-child conflict, and subjective well-being. Front Psychol 2022; 13:954330. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.954330 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ogbaselase FA, Mancini KJ, Luebbe AM. Indirect effect of family climate on adolescent depression through emotion regulatory processes. Emotion 2022; 22(5):1017-29. doi: 10.1037/emo0000899 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hickey EJ, Nix RL, Hartley SL. Family emotional climate and children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2019; 49(8):3244-56. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04037-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vasiou A, Kassis W, Krasanaki A, Aksoy D, Favre CA, Tantaros S. Exploring parenting styles patterns and children’s socio-emotional skills. Children (Basel) 2023; 10(7):1126. doi: 10.3390/children10071126 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li D, Li W, Zhu X. Parenting style and children emotion management skills among Chinese children aged 3-6: the chain mediation effect of self-control and peer interactions. Front Psychol 2023; 14:1231920. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1231920 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kirby JN. Nurturing family environments for children: compassion-focused parenting as a form of parenting intervention. Educ Sci 2019; 10(1):3. doi: 10.3390/educsci10010003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Limone P, Toto GA. Origin and development of moral sense: a systematic review. Front Psychol 2022; 13:887537. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.887537 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ma HK. The moral development of the child: an integrated model. Front Public Health 2013; 1:57. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00057 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hijazeen RA, Aladul MI, Aiedeh K, Aleidi SM, Al-Masri QS. Assessment of moral development among undergraduate pharmacy students and alumni. Am J Pharm Educ 2022; 86(10):ajpe8659. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8659 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pozo Enciso RS, Arbieto Mamani O, Mendoza Vargas MG. Moral judgement among university students in Ica: a view from the perspective of Lawrence Kohlberg. F1000Res 2022; 11:1428. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.125433.2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abbasi A, Zarei M, Omranifar D, Mohammadi M, Alizadeh M, Mohammadpour E. Coping self-efficacy and its contributing factors among medical students at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Res Dev Med Educ 2023; 12(1):12. doi: 10.34172/rdme.2023.33124 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Doménech-Betoret F, Abellán-Roselló L, Gómez-Artiga A. Self-efficacy, satisfaction, and academic achievement: the mediator role of students’ expectancy-value beliefs. Front Psychol 2017; 8:1193. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01193 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hayat AA, Shateri K. The role of academic self-efficacy in improving students’ metacognitive learning strategies. J Adv Med Educ Prof 2019; 7(4):205-12. doi: 10.30476/jamp.2019.81200 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Vahedi L, Taleschian Tabrizi N, Kolahdouzan K, Chavoshi M, Rad B, Soltani S. Impact and amount of academic self-efficacy and stress on the mental and physical well-being of students competing in the 4th Olympiad of Iranian Universities of Medical Sciences. Res Dev Med Educ 2014; 3(2):99-104. doi: 10.5681/rdme.2014.020 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hayat AA, Shateri K, Amini M, Shokrpour N. Relationships between academic self-efficacy, learning-related emotions, and metacognitive learning strategies with academic performance in medical students: a structural equation model. BMC Med Educ 2020; 20(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-01995-9 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Grøtan K, Sund ER, Bjerkeset O. Mental health, academic self-efficacy and study progress among college students - the SHoT study, Norway. Front Psychol 2019; 10:45. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00045 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thawabieh AM, Al-Rofo MA. Vandalism at boys schools in Jordan. Int J Educ Sci 2010; 2(1):41-6. doi: 10.1080/09751122.2010.11889999 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Saeedi Y, Maktabi G, Hajiyakhchali A. The relationship between school connectedness and academic satisfaction with tendency to vandalism in male secondary high school student of Ahvaz. J Sch Psychol 2020; 9(3):83-100. doi: 10.22098/jsp.2020.1066.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yousefi N, Pariyad M. The relationship between family emotional climate and epistemological beliefs with academic performance among fourth year high school students in Bukan. J Sch Psychol 2020; 9(3):307-24. doi: 10.22098/jsp.2020.1078.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Manavipour D. Construction measures for the moral development scale of students. The Journal of Modern Thoughts in Education 2012;7(4):89-96. [Persian].

- Jinks J, Morgan V. Children’s perceived academic self-efficacy: an inventory scale. Clearing House 1999; 72(4):224-30. doi: 10.1080/00098659909599398 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hosseinkhani Z, Hassanabadi H, Parsaeian M, Nedjat S. Epidemiologic assessment of self-concept and academic self-efficacy in Iranian high school students: multilevel analysis. J Educ Health Promot 2020; 9:315. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_445_20 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keshtvarz Kondazi E, Fooladchang M. The relationship between family atmosphere, school value and academic buoyancy: the mediating role of perceived self-efficacy. Quarterly Journal of Family and Research 2022;19(2):107-26. [Persian].

- Modabber SA, Sadri Damirchi E, Mohammad N. Predicting students’ mental health based on religious beliefs, educational self-efficacy, and moral growth. J Sch Psychol 2019; 7(4):143-57. doi: 10.22098/jsp.2019.752.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Cui F. Mindfulness, self-efficacy, and self-regulation as predictors of psychological well-being in EFL learners. Front Psychol 2024; 15:1332002. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1332002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]